Advocating for accurate, timely, and trustworthy fiscal information

This analysis for the Global Data Barometer public finance module was compiled by, Aura Martínez, Coordinator for Knowledge, Technical Assistance and Collaboration, Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency- GIFT. This blog is originally published by the Global Data Barometer here.

A cooperative relationship between the government and the public in the use of public resources promotes trust, transparency, and participation. For such a relationship to exist and be fruitful, governments must be obliged by law to disclose fiscal data, and information must be open, accessible, timely and of good quality.

To establish a baseline for assessing the collection, management, and reporting of fiscal data by governments around the world, the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (GIFT) joined forces with the Global Data Barometer (GDB) to include a Public Finance (PF) module in the GDB’s most recent edition. The PF Module provides an assessment of two dimensions: “governance” and “availability”. The governance dimension assesses the existence and comprehensiveness of regulatory frameworks that mandate information disclosure requirements, while the availability indicator evaluates the level of openness and public access to structured, machine-readable information.

Public Finance Module Global Scores

The PF module scores countries from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest). A score of 100, means that the country complies with most or all the requirements for its legal framework or available data to be considered “openly available to the public”, while a 0 score means that the country has severe challenges in both its legal framework and data availability.

With the highest score of 93.81 from France, and an average global score of 49.32, the PF module shows two mayor trends: (1) public financial information has been made available regardless of the existence of legal frameworks that specifically mandate it, meaning that government and civil society champions can achieve openness in action; and (2) there is a worldwide need for comprehensive and explicit public financial data disclosure frameworks, as experience has shown that the fact that champions have had some success, does not guarantee data quality, permanence or its sustainability. Both of these trends provide great inputs for evidence-based policy and activism.

Public Finance Module Scores

Source: Databases (questionnaire) of the GDB Public Finance Module. Rounded-up numbers.

Cluster and dimension comparison

Aside from the two dimensions, the GDB grouped countries/jurisdictions to promote a comparative approach. These groupings, which will be referred to as clusters, do not follow a regional approach and further research should be undertaken to provide relevant insights in this regard (full details on clustering per country/jurisdiction can be found in the GDB’s methodology).

Clustering allows us to note that there are countries that perform well in all groups: France (93.81), South Africa (93.47), Mexico (93.42), Armenia (88.27), Republic of Korea (84.62), and Egypt (49.06); that can be seen as hubs for practices and frameworks for national reformers and activists in similar contexts to find inspiration and paths forward.

Public Finance Module performance per GDB Country Group: Top, Average and Low Tier Results

Source: Databases (questionnaire) of the GDB Public Finance Module and country classification in groups according to the GDB. Rounded-up numbers. Countries in the graph represent the highest and lowest countries in each group, the average country is the one closest to the average of its cluster.

The clustering approach also shows interesting interactions between the availability and governance dimensions. As we see in the graph below, on average, most groups have higher average scores for the availability indicator, which shows that governance frameworks have further to go in terms of explicitly mandating the publication of structured, standardized, open-licensed and open formatted financial data.

Average Score per GDB cluster

Source: Databases (questionnaire) of the GDB Public Finance Module and country classification in groups according to the GDB. Rounded-up numbers.

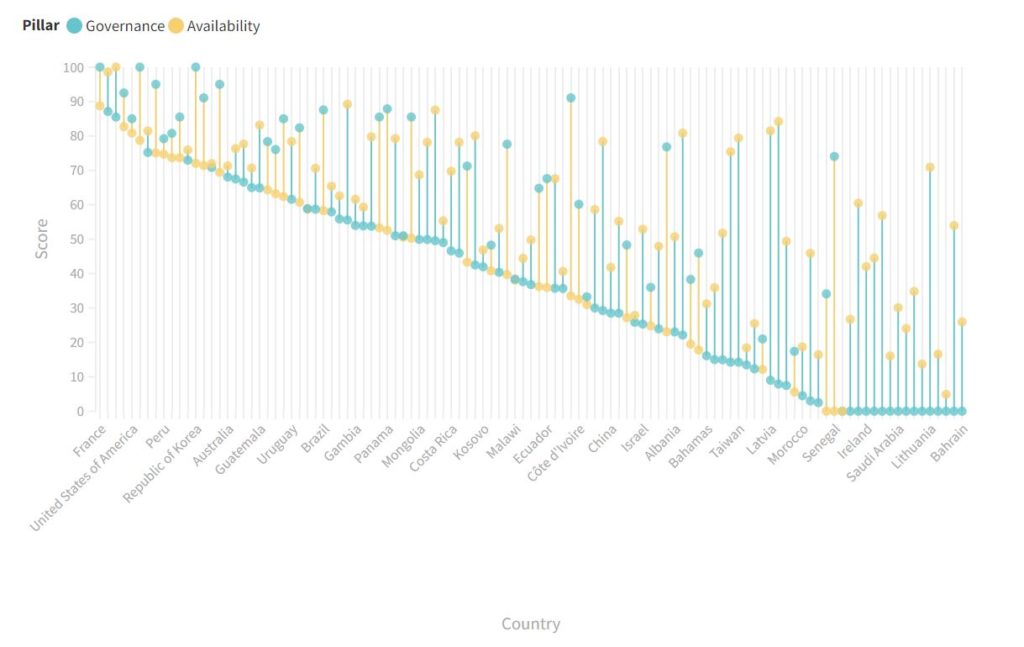

As we further compare dimensions in the graph below, we see conflicting yet interesting patterns: while some governments tend to work more on data availability than on data governance frameworks (whenever we see the yellow dot indicator surpassing the blue one), others do not comply with availability requirements even with a governance framework compelling them to do so (whenever the blue dot indicator is above the yellow one). In cases where low availability is the obstacle, many do publish information, yet it is still in pdf format, or images, including official signatures or letterheads that prevent deeper analysis.

Availability and Governance Scores Comparison

Source: Databases (questionnaire) of the GDB Public Finance Module. The graph is ordered from highest to lowest according to the lowest score (either governance or availability) per country.

What do we learn from these comparisons? That most countries are publishing important amounts of public finance information in open formats, based on specific regulation frameworks, but significant progress is still required to advance countries below the mean line in both availability and governance indicators, and that there are remarkable gaps between countries, for example, in the quality of open data and enforcement of legal frameworks, or the use of machine-readable formats and implementation of digital tools, that can be bridged through decisive governmental actions, leveraging technological solutions, cooperation with non-governmental actors, technical assistance, and peer learning.

What’s next?

As any new global tool, the first edition of the GDB PF module will continue to be refined in future editions in terms of scope and data quality. This is at the heart of an open data movement that is iterative, evolving, and always striving to push inclusive, evidence-based progress and development.

Following the publication of the GDB results, there are opportunities arising for:

- Pursuing standard guidelines to improve legal frameworks at the national level;

- Establishing or institutionalizing collaboration schemes between fiscal open data users and providers at the national level, as this push has shown to be a key driver of the availability dimension;

- Promoting technical assistance and leveraging existing networks for sharing technical knowledge through peer-learning and standard-setting exercises;

- Countries to benefit from the opportunities emanating from new technological trends and digital openings to build robust systems that better complement and support their legal information disclosure frameworks;

- The triggering of a ‘race to the top’ culture by promoting a set of standards for legal frameworks, the digitalization of public financial management, and the enhancement of cooperation between governments, the private sector, civil society organizations, and the users of data.

Public finances reveal the true priorities of governments. When undertaking accountability checks, accurate, timely, and trustworthy fiscal information is a tool against misinformation and manipulation, for better communication amongst citizens and governments, and for the fostering of trust and collaboration. It is hoped that the GDB Public Finance module inspires champions around the world to work towards these common goals that the GIFT network also remains committed to advance and promote in the countries it supports, and among all other members of the international fiscal openness community.